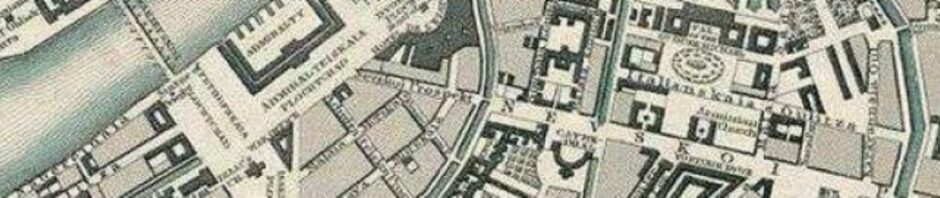

Dostoevsky moved to St Petersburg in May 1837 for his schooling, and lived in the city as a student, junior officer, writer and then prisoner, until December 1849. Following his incarceration in the stockade in Omsk and exile in Semipalatinsk, he returned to St Petersburg in March 1860 and lived there until April 1867, when he departed for Europe with his new bride, Anna Grigorevna. They returned to Russia early July 1871, and spent the remainder of Dostoevsky’s life living between St Petersburg and Staraia Russa.

Markers are numbered in chronological order. Information on Dostoevsky’s addresses is taken mainly from E. Sarukhanian, Dostoevskii v Peterburge (Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1970) [Dostoevsky in Petersburg] [pdf], with reference also to Wikimapia.

I think your last paragraph is spot on and, while it is prbbloay wise, I do not think you need to make any concessions to those traditional literary researchers [who …] dismiss this sort of project as reductive and bypassing all that is essential in Dostoevsky’s novel – its philosophical, spiritual and emotional intensity’. Even if they are hypothetical I feel they do prbbloay exist.I do not see tracing a set of coordinates in Dostoevsky as literal or reductive. It seems to me that those traditional literary researchers have gone things the wrong way round. The philosophical, spiritual and emotional intensity of a Dostoevskian novel comes through the text. After the reading. If focusing on coordinates is reductive then I struggle to see what constitutes a good reading of the text, because the coordinates are just words in the text. If they say your reading is reductive then they are simply sidestepping the issue because they have not got the stomach to do this sort of reading themselves; it is dull, it takes a long time, and success’ (for lack of a better word) is not always guaranteed. But when you collect and integrate this sort of data into a reading it makes it far better.I cannot remember whether Jacques Catteau researched it himself, or whether he was citing someone else, but why is his focus on the frequency of colour in Dostoevsky’s (and other Russian and nineteenth-century realist) texts, and his debate about whether it is semantic or symbolic, any different to your project here? In fact, yours is better because it is visual and makes it far easier for contemporary readers, especially those who do not speak Russian and have no access to specialist resources, to appreciate aspects of the text that they can only grasp at and articulate within a philosophical, spiritual and emotional’ framework. This sort of work should be encouraged generally and, if you read around other subjects, you will find that similar things are already done (there is an English work on how modernist novels map out city spaces that springs to mind, but the title escapes me at the moment, and it is not as visual as yours). For an essay on Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary last term, I counted where and when the colour blue (and various synonyms) was used in the novel*, only later to realise that there is a massive amount of research on this area already. The frequency of the colour, while significant in a way, is not what stood out. It was how Flaubert used colour to suggest the changing moods of Emma Bovary’s imagination.In your case, is Dostoevsky the thinker coming before Dostoevsky the writer, again?* I read the novel a second time to note the specific pages as I had picked up on it on my first reading. Then I downloaded the eBook and double-checked the references and noticed one discrepancy between different translations (i.e. what was blue in one translation was grey in another). Interestingly enough, this is the only thing apart from saving space on my shelf that I have found useful about eBooks so far!